Episode

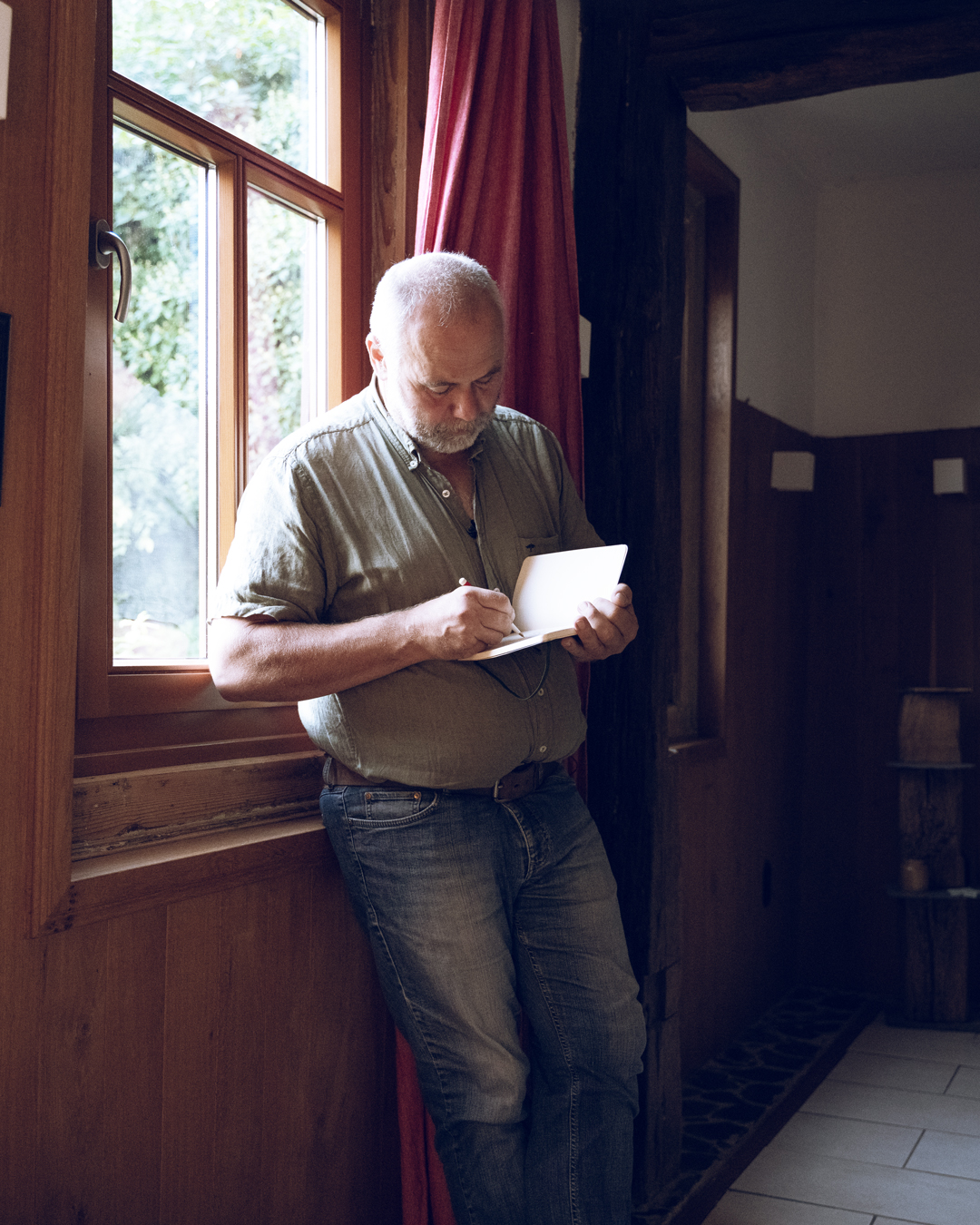

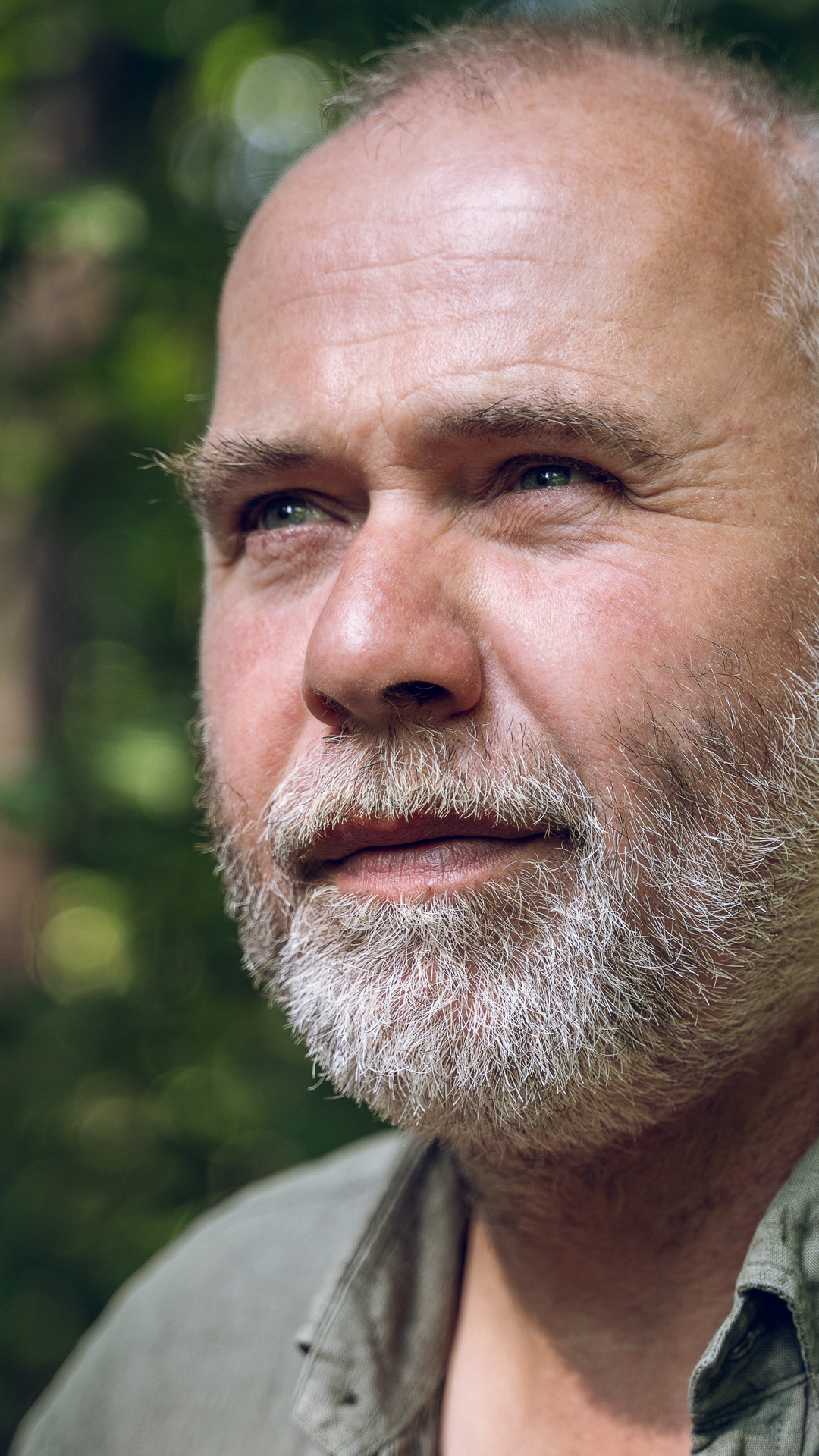

Martin Janner // Forestry and economy

The

tree writer

Martin Janner is a forester. For his work, he needs a sharp memory, imagination and vision. He must know the history of his forests in order to secure their future. That’s why Janner keeps records. For 26 years he has been writing down the date and location of the work carried out by his lumberjacks. He writes down each task in a code that only he himself understands

Mr Janner, the forest is your workplace, the trees often have neon-coloured signs. Do foresters also write on wood?

Of course! It’s, an art in itself. You need a spray can of tree-marking paint and a serious knack for graffiti. But seriously: like any proper graffiti artist, I attach importance to other people in the forest recognising my handwriting. Aesthetics play a significant role. When I let apprentices mark trees on occasion, their markings irritate me for days.

Did you have to practise to write adeptly on trees?

You have to figure out the right distance between tree and can, and do it with a certain flair. Once you have that down, some marks are really fun to make. My favourites are B and R because of their large curves. I use R, for the logging trails (Rückegasse in German) used by the forestry equipment to transport logged wood.

What do we need aesthetics in the forest for?

For the people who go there. Anyone who goes to a forest wants to enjoy nature. And it’s my job to make sure this enjoyment can be experienced in a largely unadulterated way. I’ve developed a few techniques to spray as discreetly as possible. For instance, I paint the trees that are protected for conservation – which we’re actually supposed to mark in white – in dark blue because the colour is less noticeable. Only those who are looking for it find it.

Do all foresters use the same marks or does each one develop his or her own system?

After a while, everyone develops their own idiosyncrasies. I’ve got into the habit of giving the piles of felled timber along the forest trail more than one number. I also always write down the municipality and forest section, i.e. the exact place of origin. It’s my way of paying my last respects to this timber. It’s better than stapling a barcode onto it. For me, the respect that we forestry folk have for wood as a material is expressed in our handwriting.

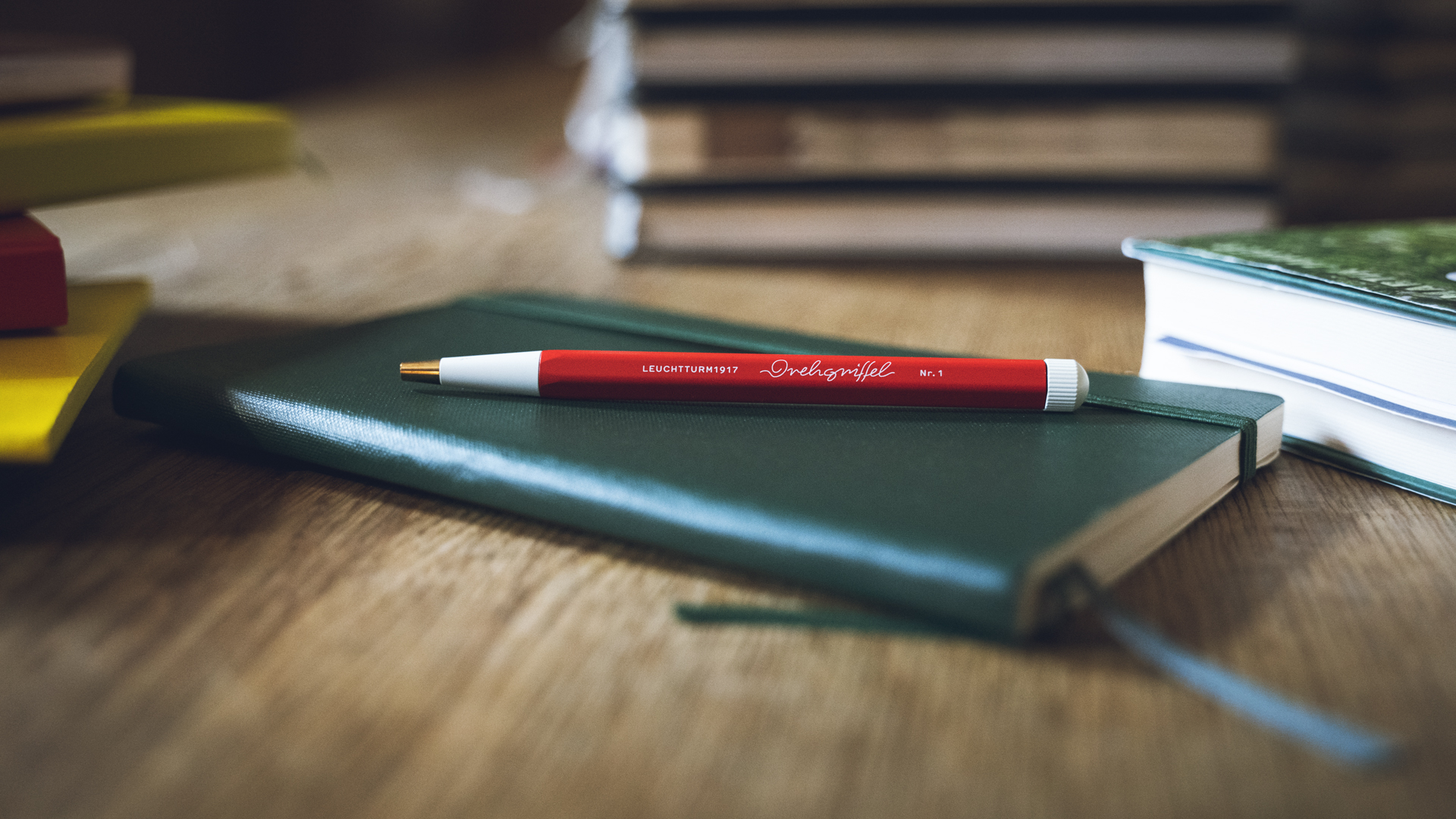

As a forestry person, I feel very connected to paper as a material.”

Do you ever think about what the timber shipped out of your forest will be used for?

Absolutely. As a forestry person, I feel very connected to paper as a material. That also has a sensory component. I know how a freshly felled tree smells; I know how it smells during pulp production and next to paper rollers; when I walk into a book shop and recognise the scent, a circle is closed for me. So paper also gives me a sensory experience, both while reading and while writing.

Do you write much on paper?

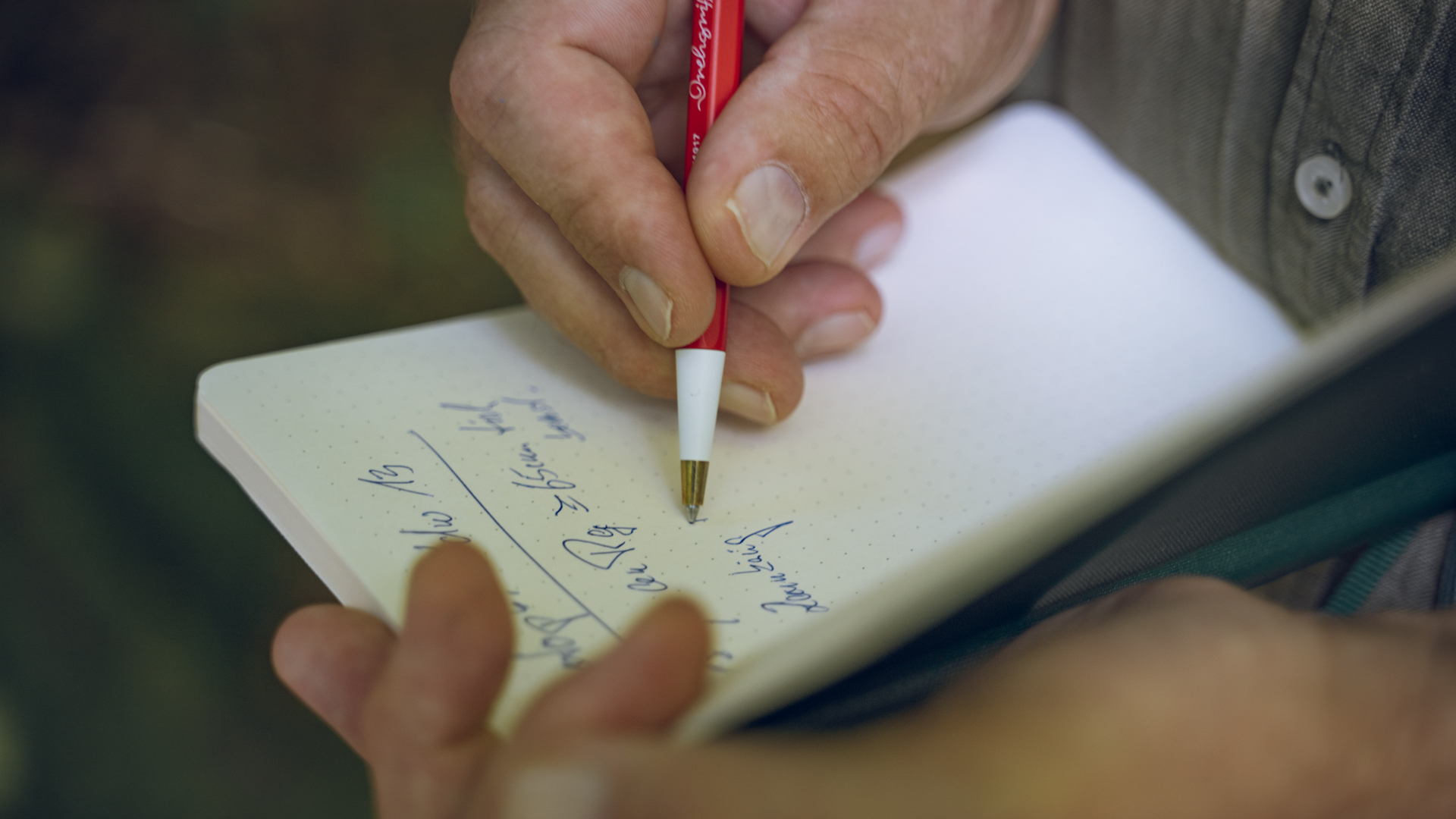

As much as possible. Memory aids, appointments, tasks – I’m from an older generation. For me, computers obliterate the senses – I feel restricted by them. When I write on paper, by contrast, my thoughts can flow freely from head to hand. For 26 years, I’ve been filling notebooks with all the things that happen in my district: the date and forest section as well as the work my lumberjacks do. I also include the amount of material used – e.g. for young plants – and what was still missing.

What do you do with these notebooks?

I collect them. They’re my personal archive and are all there on a shelf next to my desk. The shelf is currently jam-packed. I have to find something bigger...

Do you ever look through your old notes?

I love doing that! Sometimes, questions about particular forest lands come up, such as: What did we do back then that worked so well – or that didn’t? And that information can be found in codes and abbreviations in my notebook. Though I’m the only one who understands them.

I get to do a job which, thanks to handwriting, links me to decades of other people who worked in these forests before me.”

You have a secret code? Could you give me an example?

Sure, let’s try a simple one: “Rett1 TH W8”. “Rett1” means forest section 1 in the municipality of Rettershain, where a timber harvest (“TH”) was carried out and my colleague Wolfgang worked there for 8 hours (“W8”).

Do you always have a notebook on you in the forest?

Yes, and you can tell. When it rains, it gets water stained. I frequently make fingerprints with moss or dirt. Sometimes I open up an older book and find leaves or dead insects inside. And that’s fine with me, they can stay there. When I see these things and read my notes years later, I can tell exactly what was going on that day. And that certainly has something to do with taking notes. It links the information with the situation.

Is there standard lettering in forestry like there is in architecture?

There used to be, and so aspiring foresters had to do special training courses. Because ultimately, they write down a lot of things that other people have to decipher, including maps. I still have a forestry map for my district from 1887 that was labelled completely by hand. All of my predecessors added something to it. When I hold this map in my hands, I get emotional every time.

What is it that moves you?

I feel the connection to these people because I can recognise their handwriting. I deeply respected my direct predecessor, who unfortunately passed away a long time ago. A while back, I had to look into his wage records from the 1950s, and when I saw his handwriting, he felt close to me again. For me, that’s the beauty of it: I get to do a job which, thanks to handwriting, links me to decades of other people who worked in these forests before me.

Martin Janner

Martin Janner is the head forester of the Oberwallmenach forest district in Rhineland-Palatinate. In 2023, he was named “Forester of the Year”. In his book “Der Wald der Zukunft” (“The Forest of the Future”, Piper Verlag, 2023), he makes the case for sustainable and species-rich forest management. At age 14, Janner already knew he wanted to be a forester. He has been managing the roughly 1,500 hectares of his communal forest for 26 years. “I promised to take care of this forest, and I will do that as long as they let me.”